When I was a gringo-loving, traitor-child to the Cuban revolution in Havana, my readings of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer never depicted the frozen tundra I encountered upon arriving to La Crosse in February 2011, when I was considering my first tenure-track position at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. My current home is a small Midwestern “city”—by Havana standards— of approximately 52,000 people on the Mississippi River, a sort of landmark on the border of central-western Wisconsin and Minnesota. “There are no shrimp living here,” I recall thinking to myself when I finally saw the Mississippi in La Crosse. The bald eagles safeguarding freedom over the scenic bluffs and narrow prairies (a promising scenario I even imagined to be staged by the university, especially for my visit), did nothing to alleviate my shock that Twain’s legendary river had already been frozen for two months.

I also remember the faces of commiseration of my then soon-to-be colleagues when I asked about any Cubans in La Crosse. Spoiled by vibrant, multicultural Atlanta during my PhD years, my expectations for La Crosse were unrealistic, to say the least. French fur traders started La Crosse at the end of the 18th century, joined later by German brewers, quarrymen and loggers in 1856. According to the U.S census, Hispanics or Latinos of any race or origin were only 2.0% of the population in 2010. Though today La Crosse is a democratic stronghold in Wisconsin politics and we are generally not fans of Scott Walker’s ideas, it is still the sort of place where your students might take the day off on opening day of hunting season, restaurants take pride on their beer-cheese soup, and you may as well be canonized, if your second cousin played for the Green Bay Packers. None of my mentors and friends, who fearing the inexorable demise of the job market convinced me to accept UW-La Crosse’s offer, could have conceived what moving to La Crosse would entail for the only Cuban to ever pursue such greener pastures—or so I thought.

At my first attempt to interview a Marielito, he came to our meeting only for five minutes. . .”

But I was wrong, of course. There had been Cubans living in La Crosse for a while, some working for a small private college, Viterbo University, and others for two large hospitals, Gundersen and the Mayo Clinic. And of course, there were other rumors about Cubans, as a result of the Mariel exodus in 1980. In fact, over 14,000 Cubans had been brought to an improvised refugee camp in Fort McCoy, a military base 35 miles East of La Crosse, which at the time of Mariel was an Army Reserve and National Guard training facility.

At my first attempt to interview a Marielito, he came to our meeting only for five minutes, accompanied by another Cuban exile who I didn’t know. Now in their late fifties, these men had settled in La Crosse nearing the end of 1980. They had been sent to Fort McCoy because they didn’t have any relatives in the United States when they first arrived in Key West with the Freedom Flotilla. They both avoided my questions about Mariel and repeatedly rejected my offers to pay for food and beer, even when I explained they were part of a research project paid by the university. “Everyone here knows who we are, but we are good people, and we don’t drink alcohol, and we pay for our own food”—they said before they left in a rush. They could not give me any more information.

For days I struggled with my guilt as a failed anthropologist and my imprudent privilege as a white Cuban with a PhD in literature. Drunk with the excitement that I felt to find Cuban heritage in my new home, I had used that privilege to ask another Cuban exile the two most disrespectful questions inside our community: “How did you come in?” and “How long have you been here?” Sometimes, it feels as if we are all in prison, or perhaps, a bigger refugee camp full of ads. I understood the immense pain the memory of Mariel represented for these men, who could not dare to revisit those days with me. I imagined myself under the burden of the social stigmas they must have carried for 35 years in La Crosse as criminals, drunks, or simply “the Cubans,” which compelled them to reject a free beer. However, what I could not apprehend was the agony of the Cuba to which they never went back. Their Cuba is one abandoned in a disorganized rush, never returned to for fear of imprisonment of punishment, remembered for the past 35 years from the banks of a frozen Mississippi.

I forced myself to read more about Mariel. I called the military base at Fort McCoy to ask about Cubans that no American young soldiers remembered. In April 1980, a very expensive agency called the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) had been charged by the Jimmy Carter administration to oversee the processing “entrants,” which was the term used by Congress to designate Cubans during Mariel. In May 1980, FEMA opened another three camps for detention and screening of Mariel refugees at Eglin Air Force Base, in Florida; Fort Chaffee, in Arkansas; and Fort Indiantown Gap, in Pennsylvania; where thousands of Cubans spent several months of their lives.

I questioned how the literature on Mariel had skipped over these months. I wondered how this corpus had gone from detailing the political scenarios that led to the exodus to producing sociological data on the resettlement of Mariel refugees in South Florida. Other than the historical fiction that has recounted the human drama at the Peruvian embassy, the Mariel harbor, the Straits of Florida, or Miami, very few works have dealt with the fraught months many Marielitos spent at refugee camps. The study of this period, however, could reorganize not only the historical memory of Mariel, but also the geopolitical map of that exodus. Moreover, all the critical categories we have attached systematically to Mariel should reconsider the ways in which a refugee’s prolonged confinement influences latter experiences of resettlement and exile. For many Wisconsin Marielitos who were at Fort McCoy, the anxiety of coping with delayed detention turned into a depressive stage that clashed with their expectations of the “freedom” and “dream” of America.

The first 172 Cubans arrived at Fort McCoy on May 29 from the camp at the Eglin Air Force base, in Florida. On June 1, however, about 1000 other impatient Cubans at Fort Chafee, in Arkansas, were involved in a riot that put 84 of them in jail. Fort Indiantown Gap also reported violent incidents, which national media quickly turned into negative propaganda about Marielitos. FEMA then heightened security in Wisconsin, where the camp at Fort McCoy had been prepared on very short notice, but by August 13 the Cuban population had peaked at 14,360. Approximately 90% of these refugees were male, between 25-35 years of age, and with no English language skills. About 160 refugees were unaccompanied minors and an average of 900 army personnel and 1600 civilians worked permanently at the compound, which was fenced with high-security barbwire.

Life inside the camp at Fort McCoy is best reflected in two newspapers published by refugees and camp personnel, El Mercurio de McCoy and The Minor—the latter ran by a group of juvenile refugees. These unique resources not only give us a complex understanding of the anxiety experienced by Marielitos at Fort McCoy, but also are a solid testimony of their historical consciousness during their detention and the Mariel crisis. El Mercurio was a bilingual publication which ran almost daily, preparing refugees with English homework, educating them on American history and geography, offering legal, immigration, and basic health advice, and updating refugees on resettlement plans and camp population. El Mercurio also had sections on world affairs, promoted religious programming at the camp, and published songs, anthems, letters, poems and comics authored by refugees.

El Mercurio underscored social life, education and entertainment programs brought by the Red Cross to the camp, mainly as a way to boost refugee morale. Religious services were weekly organized, and there was even the wedding of Jorge Pons, 22 and Sandra Padrón Zárate, 17, celebrated at one of the churches. Refugees often volunteered to work on camp maintenance tasks, and there was a sewing and knitting club of approximately 40 women who made clothes, preparing for the Mississippi winter that fortunately some didn’t have to endure. Fort McCoy Marielitos opened their own radio station, “WRPC: La voz de la libertad,” produced musical shows with their 15-piece salsa band “Los aires de la libertad” and created an Afro-Cuban folkloric dance troupe, which performed at several venues in Minneapolis and UW-Madison. There also was a group of artists, which created a large collection of paintings, sculptures and other artifacts owned by John Satori, who worked at Fort McCoy as a volunteer dentist. Today Satori is the owner of Satori Arts, La Crosse’s high-end antiques store. Juveniles at the camp were avid boxers, soccer, chess and baseball players and held regular tournaments with local high schools. Seven refugees even travelled to La Crosse to try-out with the Milwaukee Brewers, and three of them signed contracts with professional teams in Milwaukee and Sparta. El Mercurio portrayed these refugees’ activities outside the camp as positive ways to gain visibility with potential sponsors for the rest of the detained Cubans. In the paper, these artists and athletes were described as “individuals of great merit” who served as ambassadors to the American public.

Almost as if the editors knew the harsh realities of discrimination that awaited refugees outside the camp, El Mercurio regularly wrote profiles on notable Marielitos, highlighting their successful past at the University of Havana, or their artistic talents, and always clearing up any history of incarceration in Cuba by explaining the unfairness of life under Castro. The imprecise translations from English to Spanish and viceversa, improvised by camp volunteers (mostly area high school Spanish teachers and college students) allowed FEMA, U.S Army and volunteer personnel at the camp to participate in El Mercurio; and stories ran about the growing friendships between refugees, soldiers and volunteers which often paralleled Cubans to the Americans. But, more than anything, El Mercurio published editorials and letters directed at appeasing the refugees and urging them to be patient, to organize in councils and groups, to avoid violence, and to show their indebtedness and gratitude for Jimmy Carter. Permeated by the fear of isolation and the illusory discourses of the American Dream, El Mercurio reveals both, an attempt to continue the narrative of a Cuban life interrupted, and the Marielitos’ desperate cry to be seen and understood, as detention prolonged and became more bureaucratic.

Fort McCoy was also seen as the most unmanageable of all Mariel refugee camps. On September 4, a Fact Finding Commission charged by then Wisconsin Governor Lee Sherman Dreyfus described conditions at Fort McCoy in this way: “Internal Security for the protection of Cubans in the compound is for practical purposes nonexistent. Cubans are inside the compound with no protection afforded them by the U.S. government.” The commission also had found “substantial evidence of sexual and psychological abuse of both male and female Cuban juveniles.”[i] Indeed, while many refugees had no family in the United States, others were classified as “harder to place” simply for being young males, or due to rumors of their criminal records. For instance, data collected among the minors who eventually were sponsored by Wisconsin families, shelters and child fostering facilities revealed that out of 145 placed juveniles (ages 14-18), only 6 were women, only 46 had completed 10th grade, and 116 had been incarcerated in Cuba at some point.[ii]

Many of the older refugees at Fort McCoy had been political prisoners in Cuba; some were Jehovah Witnesses, some were homosexuals, and many, especially juveniles, had been incarcerated under the “Ley contra la vagancia” (Cuban Loafing Law) of 1971, or simply had been involved in black marketeering of rationed commodities in Cuba. The conflicts at Fort McCoy, on the contrary, were mostly caused by the bureaucratic federal policy for resettlement plans, and the fact that FEMA officials in Wisconsin had opted for a “self-government approach” inside the camp, allowing the creation of internal refugee security forces. FEMA relied on the “warhawks,” who later became the “águilas,” (barrack bosses, who wore jackets donated by UW-Whitewater displaying the school’s mascot, a warhawk, and were allowed to carry knives, broom sticks and clubs) to keep the order in each of the barracks and maintain communication between U.S federal officials and Cubans. The ineffectiveness of this system became evident when several extortion and sexual abuse accusations led to the “águilas” group, which was replaced by an unarmed refugee council in late August 1980.[iii]

In the meantime, Wisconsin press used these and other stories to construct a negative image of the Marielitos. Articles intersected Cuban refugees’ stories with national debates about sexual “deviancy,” economic recession, the cost of refugee resettlement programs to taxpayers and public dissatisfaction with the Carter administration. The reality at Fort McCoy, however, was that juvenile refugees escaped, or started altercations, simply to call attention on the dysfunctional system implemented for their resettlement. A story told years later, in 1985, by former refugee Roberto Hernández detailed his escape from Fort McCoy along with fellow juvenile refugee Eddy Guerra Pérez. The escape had been orchestrated by David Morgan, the coordinator of education services at the compound, who was planning to sponsor Roberto, and Major Looney Poole, one of the camp’s Army civil affairs officers. The Americans worked together to drive Roberto and Eddy to Sparta, so they could be taken into custody by a judge. In Cuba, at age 16, Roberto also had pretended to be a criminal to avoid being drafted by the Servicio Militar Obligatorio. He spent a month in jail before the police took him to the Mariel port.[iv]

By the closing of the camp at Fort McCoy on November 3, a total of 3,236 unplaced refugees had been periodically transferred to Fort Chafee, in Arkansas, which remained opened until February of 1982.[v] About 60 refugees who were considered mental patients were sent to mental health facilities in the East coast, and 84 juveniles remaining at the camp were moved to cabins in Wyalusing State Park, in Prairie du Chien. About 180 Cubans settled in the La Crosse area. However, resettlement in La Crosse, and the towns of Tomah, Holmen, Onalaska and Sparta became extremely problematic between 1980 and 1983.

Lene came in the Mariel Boatlift at age 16. His real name is Lenin, but he changed it to “Lene,” fearing reprisal against communism in the United States.”

In March 1981, the La Crosse Police Department had received over 400 complaints involving Cubans, while the La Crosse County Circuit Court had processed cases for 55 Cuban refugees.[vi] In many instances, there were confrontations between Cubans, law enforcement officers and residents. The majority of cases were misdemeanor charges for disorderly conduct at bars, carrying a knife, trespassing property, or driving without a license. But there had been a few cases of sexual assault, and one murder case in Tomah, in which refugee Lene Céspedes-Torres was convicted for the murder of his sponsor Berniece Taylor. On September 3, 1981, Céspedes-Torres was sentenced to life in prison and sent to the Waupun Correctional Institution, in Wisconsin. He writes the blog “Lene Stranded from Cuba” where he maintains his innocence based on what he asserts was inconclusive evidence and unfairness in his trial process. Lene came in the Mariel Boatlift at age 16. His real name is Lenin, but he changed it to “Lene,” fearing reprisal against communism in the United States.

Kathleen Mann was the lawyer who represented Lene Céspedes-Torres and many other Mariel refugees; so many, in fact, that she became known as “the Cuban lawyer” in La Crosse. Mann described Cubans as “adult individuals at a tremendous disadvantage” and victims of “sublimated anti-Cuban feelings,” emphasizing that most violations registered for Marielitos had been the obvious result of a lack of comprehension of U.S laws by the immigrants and their inability to communicate in English with the authorities. Terry Benson, a probation officer who also worked on many Cuban cases, explained that the lack of adequate treatment and bilingual therapists had negatively affected Cubans on probation.[vii] In an interview with Chief of Police Ray Lichtie on March 1981, he described a “Cuban preoccupation with knives,” how several Cubans had been “allegedly found in women’s apartments” but never accused of stealing, and 12 police reports which recorded fights started by angry La Crosse residents.[viii]

But even the Marielitos who had been accepted into educational institutions and spoke some English struggled to be welcomed in La Crosse. For instance, in February 1982, 29 Cuban refugees who were studying ESL at Western Wisconsin Technical Institute (WWTI), a small technological college in La Crosse, filed a complaint for racial discrimination against the school’s administration. The Cuban students wanted to attend class with refugees from other nationalities enrolled at WWTI, because the school had isolated the Cubans into the old La Crosse YMCA buildings. They were also demanding that the La Crosse County Board drop a rule which required daily class attendance in order to be eligible for a $226 monthly welfare assistance check. This rule applied only to Cuban refugees. Even when some of the Cuban students returned to class after a five-day boycott, the ESL program was closed a month later due to “poor attendance.” In 1980, a total of 91 Cubans had been enrolled at WWTI. In 1981, the number had dropped to 49. In 1982, only 2 Cubans finished two-year technical training programs at WWTI and only 14 were able to find custodial and cleaning jobs after ESL classes. In 1980, Viterbo University sponsored refugees Lorenzo Sánchez Rojas and Angel Arcario González out of Fort McCoy, and gave them scholarships to live at the college during fall 1981, but the Cubans dropped out a year later. Miguel Angel Narbona, another juvenile who was a survivor of a stabbing incident at Fort McCoy became the first refugee to enroll at Sparta High School. According to his sponsoring family, Narbona had grown “capable of serious crimes because of his violent temper” when he moved from Sparta to La Crosse to attend beauty school, after graduating high school. Narbona was on probation for the sexual assault of a 24 year-old La Crosse woman who had accompanied him to his apartment after a few drinks. Five months later, he violated his probation when, according to the La Crosse Tribune, he “attacked a man” outside WWTI on his way to school. Consequently, Narbona was sent to a federal prison to serve four years. On the last letter Narbona wrote to his sponsors in Sparta, he expressed his desire to be voluntarily deported back to Cuba.[ix]

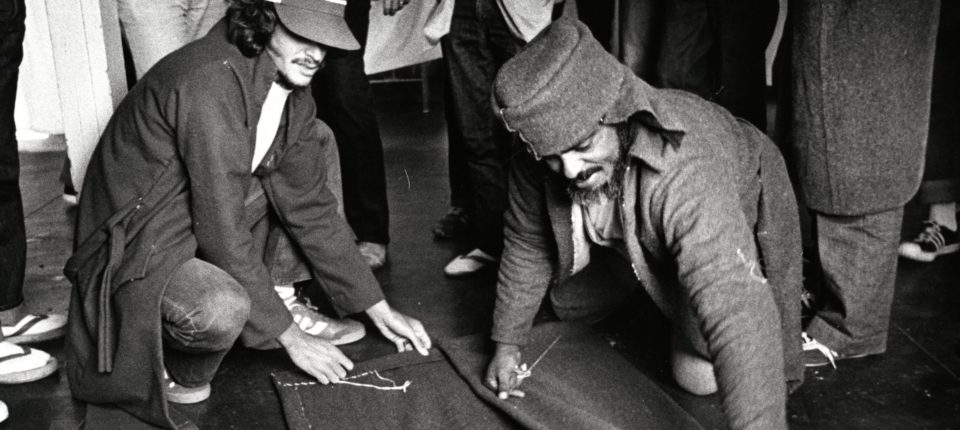

The trauma experienced by Marielitos at Fort McCoy and the prejudice they encountered later in the La Crosse area during the early 1980’s is a narrative of displacement, which I am incapable of giving justice to in my writing, for its depth, and the colliding human tapestry it represents. Photographs from that period offer more reasons to investigate the discriminatory contexts where young individuals like Céspedes-Torres, Narbona and many others were convicted, ostracized, or simply misunderstood. I bring these photographs to Cuban Counterpoint readers (courtesy of the La Crosse Tribune and the Special Collections Archives at UW-La Crosse Murphy Library) primarily as a tribute to the refugees at Fort McCoy, those I know in La Crosse, and those whom I will never meet by our often frozen-over corner of the Mississippi.

Featured Image: Cuban Refugees Board Greyhound Bus. LaCrosse Tribune newspaper, 30 Sept 1980.

All images, property of the LaCrosse Tribune newspaper, and on hold at the University of Wisconsin Lacrosse Library’s Special Collections.

NOTES

[i] “Panel urges security boost at Fort McCoy” The Milwaukee Journal. September 3, 1980.

[ii] Tans, Elizabeth. “Cuban Unaccompanied Minors Program: The Wisconsin Experience”. Child Welfare. Vol LXII, No 3, May/June, 1983.

[iii] “New refugee security group formed at fort” La Crosse Tribune. August 22, 1980.

[iv] “Aneurysm, red tape fail to break refugee’s spirit.” La Crosse Tribune. June 2, 1985.

[v] “Cuban Refugee Crisis.” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Web. (Accessed November 1, 2015)

[vi] “Crime wave followed Cubans.” La Crosse Tribune. June 2, 1985.

[vii] “Overreactions seen by Cuban actions” La Crosse Tribune. May, 8, 1981.

[viii] “Refugees linked in rise of area crime rate” La Crosse Tribune. March, 8, 1981.

[ix] “High hopes, aspirations ended in jail” La Crosse Tribune. June 2, 1985.