Cuba does not do Columbus Day. Otherwise known as El Día de la Raza (“Day of the Race”), El Día de la Hispanidad (“Day of the Hispanic Civilization”), or El Día del Descubrimiento de América (“Day of America’s Discovery”), the holiday celebrating Columbus’ arrival in the Americas began in Argentina in 1918, and from there spread through the continent. Unlike most of Spain’s former colonies and the United States itself, which made Columbus Day a Federal holiday in 1937, Cuba never joined in on the tradition. Prior to Columbus Day’s onset, however, Cuba already had a long history of Christopher Columbus celebratory discourse, parades and related kitsch. I suspect that Cuba experienced what I will call “Columbus-fatigue” a bit before the rest of the Americas.

At this point, please allow me to provide full disclosure: Columbus Day is not my holiday either. In 1992, I worked as a “bread, butter and beverage waitress” for a family resort in the Poconos, a forested locale of Northern Pennsylvania and New York State. Once every week that year, we staged a theme night celebrating the quincentennial of Christopher Columbus’ first voyage—the one that unintentionally landed in Cuba. The theme night at the Poconos restaurant was far worse than it sounds. I vaguely recall grandiose ice sculptures of the Niña, Pinta and Santa María with a surrounding salad bar and an extensive shrimp platter. More vivid in my memory are the owners of the resort who dressed as King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. A few of the resort’s executive office staff pretended to be members of the Spanish royal court. The manager of the restaurant was a knight. The smart, long-term waitresses at the resort arranged to take that night off. I was a peasant.

The Columbus theme night was a huge hit with the customers. That was understandable: people have long loved Columbus. Earlier, outspoken, privileged (or hegemonic) generations have taught us to cherish the neat origins myth that Columbus provides. Certainly, back in 1992, my employers used Columbus rhetoric to make me understand my place in the world and in service to popular history. With respect to Columbus Day this October, I thought it might be useful to take a small tour of some of the Columbus-themed early twentieth-century, Cuban, photomechanical postcards that I have since collected. These items represent both Columbus’ legacy and Cuba’s early twentieth-century descent into “Columbus-fatigue.”

I have several “Souvenir Folders,” or miniature postcard collections, that indirectly commemorate Columbus’ fall from grace in Cuban history. These folders are some of the cheapest postcards that I have, and today’s vintage market does not really embrace these over-produced, generalized history postcards. To clarify, sometime in early twentieth-century Cuba, Christopher Columbus became too broad a subject to be appreciated by increasingly discerning audiences. In these nicely packaged, convenient, surveys of Cuban history, however, Columbus always appears at the very start. For example, in one 1937, 375-word summary of Cuba’s entire history, Columbus received the first two sentences out of eighteen total. That is fairly weighty, considering that the native Taíno, already living on the island for untold centuries, receive no mention at all. Back in the 1930s, Columbus’s short history was familiar enough to attract large audiences and convince them to purchase the postcard collection as a souvenir.

Cuba experienced what I will call “Columbus-fatigue” a bit before the rest of the Americas

Peppered throughout Cuba are still a fair number of colonial-period tourist monuments dedicated to Columbus. Many of these are not popular anymore. In particular, beginning in 1826, Havana’s El Templete served untold numbers of Victorian tourists as a memorial chapel dedicated to Columbus.

The “chapel” is not a site where Columbus actually ever visited in Cuba. However, it is where, in 1519, the Roman Catholic diocese of San Cristobal de la Habana was consecrated. More than ever before, the Vatican remains adamant that Christopher Columbus will still not be canonized as a saint. Havana’s diocese has long skirted this issue as it celebrates Columbus’ sainted namesake. It probably does not matter much these days because, in any number of guidebooks, the only listing for any “El Templete” is one of Havana’s better reviewed paladares, or privately owned restaurants.

More than one of my postcards label Habana Vieja’s still very much beloved Spanish colonial cathedral as “Columbus Cathedral.” Numerous early twentieth-century photo postcards depict close-up images of Columbus’ temporary tomb that was, for some time, housed therein. Notably, today, Columbus’ former tomb is rarely mentioned in guidebooks. One image here explains that Spain kept his remains there from 1796 until 1898. These years offer significant insight into Spain’s colonial anxieties. The United States became independent from Great Britain in 1776, and Haiti was well-embroiled in its revolutionary action against France throughout the 1790s. For more than a century, Spain was terrified of losing its colonial empire—and Habana Vieja, with the Cathedral positioned just there, served as the initial port of call for ships crossing the Atlantic. Columbus’ remains were a symbolic reminder of Spain’s colonial “rights” to all of Latin America. However, once Cuba’s independence became imminent, Spain packed Columbus’ remains back to a monument in Seville.

“Niche where Columbus Remains were.” American Photo Studios, Zenea (Neptuno) 43. Circa 1901-1915. Real Photo Postcard.

In the aftermath of Cuba’s independence from Spain, Columbus’ empty Havana tomb perhaps serves best to illustrate how generic Columbus’ history has otherwise become to Cuban national audiences. There are no surviving portraits of Columbus from his actual lifetime anywhere. Eighteenth and nineteenth-century images that are still in place in Cuba, or ones that occasionally continue to appear in cigar labels, indicate that he offered audiences a figure of a heroic, but generic, every man. Whether in illustration, painting or sculptural relief, his physical characteristics are those of men from stale dominant discourse—he appears to have been Caucasian, plain looking and forever middle-aged; that’s not necessarily incorrect, but over the course of the twentieth-century, that has become a bit boring. There is very little information to nuance Columbus’ character for contemporary, post-modern generations. It appears even Columbus’ possible sexually transmitted diseases and illegitimate child are just rumors.

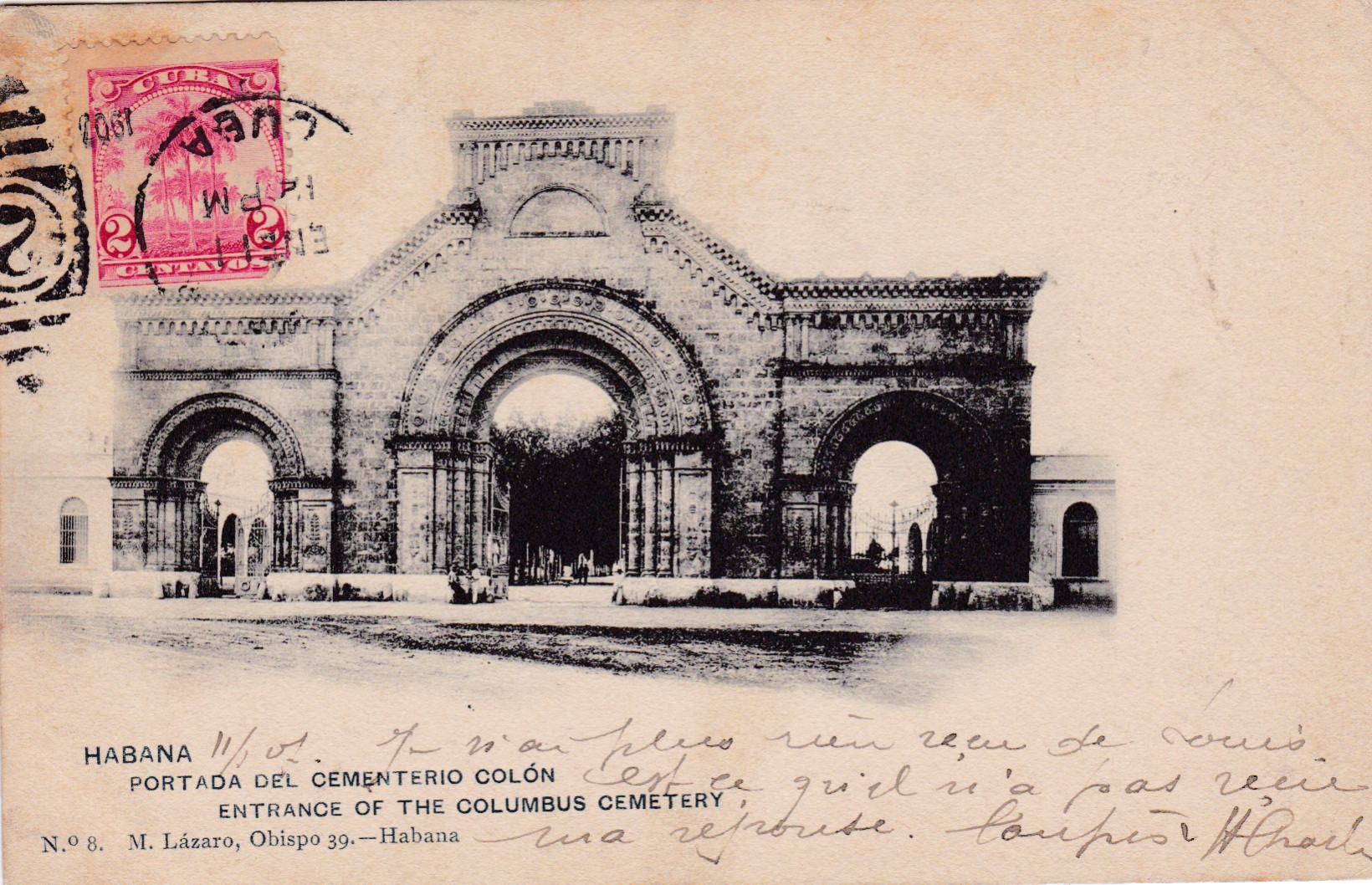

Overall, for more than 500 years in the Americas, Columbus has served as a symbol of colonial power and rather extreme social stratification. Although Cuba has never had a specific holiday celebrating Columbus, more recently, other Latin American nations have been discontinuing the holiday in favour of better recognizing indigenous populations. In the United States, a few individual state governments, as well as cities, also followed suit, including Hawaii and South Dakota. In Cuba, the most popular, ongoing tourist venue—for both Cuban and international visitors—labelled with Christopher Columbus’ name is arguably Havana’s Cementerio Colón. However beautiful and tragic this cemetery is, it is clearly walled-off and delineated as part of the past, or that which we bury and move beyond.

All images are property of the author. All Rights Reserved.