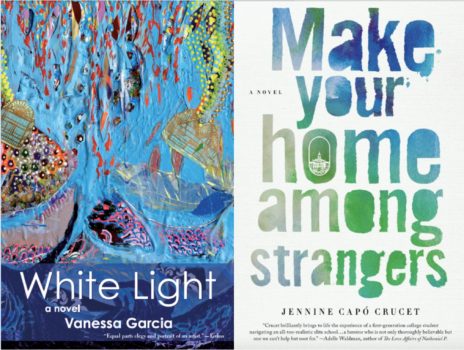

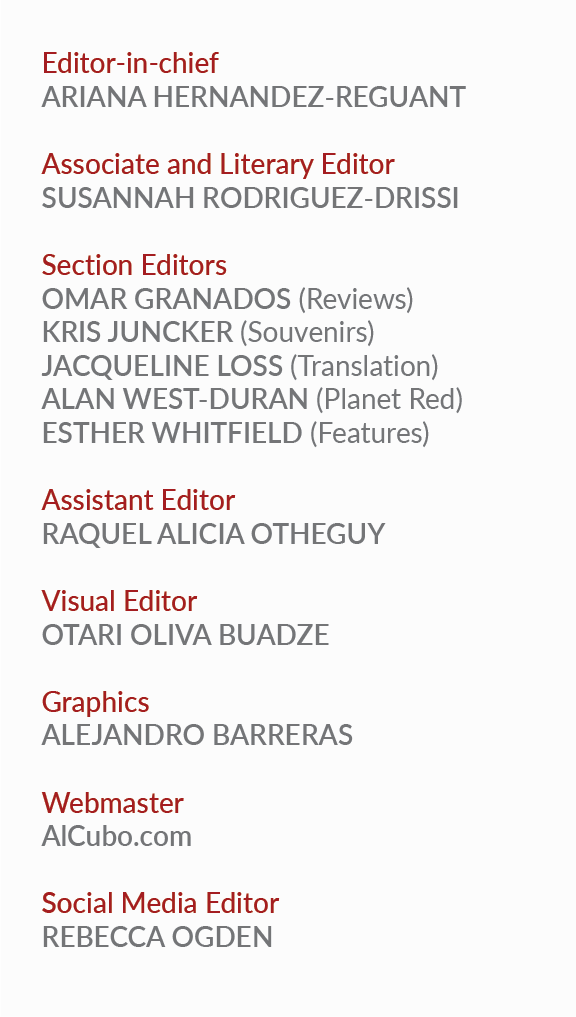

Until recently, the main concern of Cuban-American fiction has been to voice first-generation narratives about burdens of exile. Inherited through family story-telling, these stories were central to epic narratives that originated in an island yet to be experienced first-hand. In this respect, Jennine Capó Crucet’s Make Your Home Among Strangers (St. Martins Press, 2015) and Vanessa Garcia’s White Light (Shade Mountain Press, 2015) depart from their literary predecessors. The physical and emotional journeys in Make Your Home and White Light are the authors’ own, and they do not begin in Cuba, but in the United States.

From these two novels emerge narratives that resound the death knell of Cuba nostalgia. As the respective protagonists disperse and come in contact with the wider stream of U.S. cultures and experiences, so does Cuban-American fiction sever the metaphorical umbilical cord that kept it tied to the island and the life its forebears left behind. The result is two stories that, in different degrees of separation, move away from Cuba as their point of reference to relay an experience in tune with an American-born generation and that breaks away from its origins. In doing so, Make Your Home and White Light express some of the same concerns one finds in novels such as Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club (1989), Chang-rae Lee’s Native Speaker (1996) and, most recently, Edwidge Danticat’s Untwined (2015), to name only a few.

These two novels represent emancipation into an “American” fiction that, invariably, is a life or two away from an original elsewhere.

Jennine Capó Crucet is the first American-born child of a Cuban family in Hialeah, a mostly Cuban immigrant city in the outskirts of Miami. Inspired by both her family stories and her own experiences, her short story collection How to Leave Hialeah (2009) won her praise and prizes in the writing world. Of the same generation, Vanessa Garcia too was born to Cuban-émigré parents in Miami. She is a multidisciplinary writer, scholar and artist and White Light is her first novel. From Capó Crucet and Garcia’s cultural and generational bonds, however, spring radically different approaches to language and to the roads they take to inch away from the past.

While Capó Crucet’s writing exhibits a knack for humor, a sauciness, and a lack of pretense that are always disarming, Garcia’s narrative is lyrical, more measured—self-conscious in a way that borders on memoir. For both of them, however, the past is a temporal, emotional and psychological state that must be reckoned with, only to be left aside, in favor of an urgent present. Both their novels are coming-of-age stories that tend to the young women who discover their own voice amidst the pressures of life, love, and work. Rather than point to identifiable ethnic experiences, these workss fess up, sometimes in graphic detail, on the things that we women do behind closed doors, that we don’t tell our neighbors, that we keep from our parents: sex in cars, oral sex, masturbation, bulimia, self-doubt, and the risks we take along the way. To read these novels together, then, is to surrender to youth’s journey.

Make Your Home Among Strangers follows 18-year-old Lizet Ramirez from Miami to college in New York state. At home, Lizet’s life has turned chaotic. Her parents split up, her unwed sister is pregnant, and her father sells their family home and moves out—a decision that lands Lizet, her sister, and her mother in a cramped apartment in Little Havana. Against her mother’s wishes, and perhaps eager to flee her situation at home, Lizet decides to set off for college. Once there, she’s suddenly forced to deal with who she is and where she comes from:

Oh, they’d say, But where are you from from? I was from Miami, but eventually I learned to say what they were trying to figure out: My parents are from Cuba. No, I’ve never been. Yes, I still have family there. No, we don’t know Fidel Castro.

As Lizet’s musings make clear, it is only when confronted with “American” society that she learns to conform to politics of identity—in other words, she learns to fulfill the categorical expectations of her “American” peers. A fictionalized Rawlings College in New York, then, represents the place where she learns to define her belonging within a larger community of U.S.-born Cubans in particular, and Latinos more generally. At Rawlings, Lizet rubs elbows not only with Jillian, her “white” roommate, but also with those identified as “students of color.” While attending a mandatory Diversity Affairs welcome meeting for minority students, Lizet meets Dana, a student from Texas, with an Argentine father and an American mother, as well as Jaquelin Medina, a “half-Mexican, half-Honduran” student from Los Angeles. These and other encounters do much to challenge what she knows about the world, defined until recently by the insularity of her Cuban community in South Florida. For instance, when Jaquelin confesses that her mother does not have legal status in the U.S., Lizet wonders if Jaquelin’s mother could also take advantage of the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act that grants Cubans exceptional benefits by leaving the U.S. and returning “via raft as a Cuban, so that in four years she could easily board a plane and fly out to see her daughter graduate from one of the best colleges in America.”

Ultimately, ill-equipped for the social, cultural and academic demands of college life, Lizet struggles to make a home for herself among the strangers she meets in college. Ironically, through the kind of critical distance that she has acquired, her loved ones become strangers too. In fact, by then, home poses a new set of problems. When, on Thanksgiving day, Lizet knocks on the door of her family’s apartment, dinner (or some Cuban version thereof) is ready, but instead of a warm reception she finds her sister wrapped up in the wares and cares of a toddler and her mother entranced by local news. Ariel Hernández, a Cuban refugee boy—a fictionalized version of Elián González—has been found clinging to a raft at sea, becoming a pawn in a binational custody battle that mirrors Lizet’s own conflicted identity. She returns to college after the break, only to return home when summer comes around, joining her mother at one of the rallies for Ariel. Lizet is then pulled apart by her loyalties to her Cuban-American community, her struggle to understand her mother’s anti-Castro fervor, and her own desire for emancipation. Finally, and not without difficulty, Lizet opts to give her own life a chance by, merely, walking away once again.

Then as well, Vanessa Garcia’s inaugural journey in White Light also begins in Miami, but her journey takes her not to a rural college but to the bustling center of New York City, approximately seven years after the 9/11 attacks on Manhattan. While Capó Crucet’s rural New York is ahistorical and personal, Garcia’s urban environment constitutes a geohistorical and political referent. With 9/11 in the recent past, any original Cuban trauma is shadowed by a new, much greater threat that overrides all other ideological wars, including the Cold War.

White Light opens with the news that Veronica González, the Cuban-American protagonist and a visual artist, has been offered a solo show during Art Basel, Miami’s renowned international art fair—a rare opportunity, and one she’s been waiting for to transform her life, in Veronica’s words, “Oprah makeover-style.” At her art dealer’s request, Veronica takes a flight to New York City to settle the details of the show, still some months ahead. “If you get your painter ass up here,” Lee tells her, “it could change your life.” On the plane to the city she called home at the time of the 9/11 attacks, she obsesses about a passenger she finds suspicious:

I look down at my Art in America, ignore him—try to, anyway. Except that his green jacket keeps whaling around and flinching. He’s looking up and down the aisle now. Up and down, up and down. Rubbernecking. The kid has a massive book in his lap I can’t quite catch the title of. The thing is a tome, could knock someone out flat with that brick. Jesus, I hope it’s not the Koran.

She only finds her anxiety allayed when the young man she fears asks the flight attendant for a beer, which she sees as an improbable choice for an Islamic terrorist. Her preoccupation, however, marks her not as a Cuban but as an American, in a journey filled with references that seek to make her life not a Cuban story, not an exile story, but an American story.

But as it happened to Lizet, events at home pull Veronica back. Her obese father is found unconscious in his Miami apartment and, upon returning, she is forced to deal with a situation that jeopardizes both her personal and professional life. What at first appears to be an emotional and psychological set back, however, ends up being the catalyst for Veronica’s true journey—a journey toward creativity, personal and professional growth, wherein the painful past that her father represents becomes instrumental. Yet aside from the mention of Cuba as her father’s point of origin, and various Spanish words peppered throughout the novel, Veronica’s national background is incidental to a story that takes place in Miami. Neither the writer nor the characters ever suffer from bouts of Cuba nostalgia nor does Cuba ever become a central point of reference for either the characters or the narrative itself. In fact, unlike Capó Crucet’s Lizet, Veronica struggles very little, if ever, with her Cuban-American identity. She struggles with an eating disorder, with the death of her father, with her life as an artist, and with the end of a romantic relationship—but her family origins are inconsequential, as she learns who she is and what she wants out of life.

When her father dies, Veronica is haunted by the conflicted relationship they had. Unable to paint, and overwhelmed about it, her solo show during Basel is in jeopardy. The opportunity to move forward comes—and so will recovery—but only at the expense of another unexpected loss in her life: her lover, Tony, breaks up with her. Devastated, Veronica makes the decision to move into her late father’s apartment and it is among his things, the wallpaper, the disappearing smell of her father’s wallet, that she begins to journey back to herself. To that end, she paints the walls white: “the color of new beginnings. Tabula rasa. A blank canvas.” As if suggesting that moving forward always entails a reckoning with the past, Veronica’s show at Basel ends up including material traces of both her father and 9/11. The past may still throb and ache like a phantom limb but, as Veronica reasons, “that doesn’t mean [she] can’t keep walking.”

Neither Vanessa Garcia nor Jennine Capó Crucet respond to their past in the same way, but in neither case is the past an island in the mist. Instead, the past is the starting point to exert an individual agency that—because they are American—is greater than the burden of their family heritage. In this process, their novels themselves constitute a rite of passage, a coming-of-age for second-generation immigrants who happen to be Cuban-American. Their literary characters’ individual journeys parallel that of their authors into the bigger shelf of American life and fiction. As such, Make your Life and White Light contribute to the understanding of “Americanness” in the making. Together, Capó Crucet and Garcia would seem to suggest that there’s nothing more powerful than the stories we choose to tell—except, of course, for the ones we choose to leave behind.

Make Your Life Among Strangers

Hardcover: 400 pages

Publisher: Martin’s Press; First Edition (August 4, 2015)

ISBN-10: 1250059666

White Light

Paperback: 284 pages

Publisher: Shade Mountain Press (September 23, 2015)

ISBN-10: 0991355547