In 1976, a fourteen year-old Romanian gymnast named Nadia Elena Comăneci scored a perfect 10 for her performance on the uneven bars in the Montreal Olympics. Until then, no gymnast had ever received a perfect score; in fact, the electronic score board was not programmed for such a triumph, thus the judges’ unanimous decision appeared as a 1, confusing the attending crowd momentarily. I don’t remember her performance much—or, perhaps I missed it entirely. Four years later, however, I sat on a child-size rocking chair inadvisably close to a black and white television and watched, eyes pegged like darts on the small screen, as the young Romanian, now 18, won another gold medal at the Moscow Summer Olympics. Since WWII, Soviets and East Europeans had dominated world gymnastics—evidence, for many, of the triumph of women’s sports under the patronage of socialist regimes. For me, however, Nadia’s performance that summer had a much more personal impact.

It was 1980 and fishing boats and other vessels ranging in size from 18 to 90 feet pushed, shoved, and dropped hook into the Mariel harbor. My aunt had rented a shrimp boat and hired a captain. We waited to be taken away to some place I only knew by name: California. Life in Bauta, what was then a small province of Havana, had proven to be mostly sweet. I didn’t want to leave. Nadia, in her short dark bob, bangs framing her face, perfect balance—in spite of the back and forward flips her performance demanded—seemed to offer a way out.

Long before I’d seen her on the beam or performing the floor exercises, I’d tried my luck at cartwheels. I was never any good. My legs always crooked in the air. But I was a good dancer, and I loved watching her move. Charming and feminine in a way I didn’t think possible until then. I’d been taught to sit with legs padlocked at the knees to avoid showing my underwear. Learned that a female body should be supple and devoid of sharp edges. Nadia was strong and feminine both at once. I imagined her playing with boys on my street and leaving them with mouths agape, as she’d twist and flip right before their eyes. Walking on her hands in a pionera uniform and flaunting her skivvies in the sun. All along, her bob a practical choice. Hair that never once got in the way. Hair that stayed in place.

You want to be a gymnast?” She asked. “No,” I said. “I want her hair.”

In 1980’s Cuba femininity was still measured, in many ways, by the length of a girl’s hair. Short hair was for tomboys. Girls who, unlike me, took to the streets to play like boys. Like Elenita, a beautiful girl with tanned skin, emerald green eyes, and a boy’s white, button-down shirt. Braless, when cultural norms demanded that her small pubescent breasts be restrained. And, of course, with short hair. Evidence, it was always implied, of her parents’ lack of care, and her knack for behavior that confused the required division between genders. My hair was long. My crowning glory. Brushed to a lustrous deep brown by my mother; yanked by my grandmother all the way to the bathroom whenever I threw myself on the floor, stiffening my body and refusing to bathe; gathered into one single pony tale when the heat was too much to bear; and rinsed with chamomile tea on most occasions to encourage natural highlights. My father’s pride and joy, as had been my mother’s hair, until the day she chopped it off—God only knows why. I can only assume it was the scarcity of hair products, or the heat, or the fear of reprisal for leaving, or some sort of rebellious gesture against my father’s authority. In any case, my father expected me to reach California with my head of hair intact. There was little left to do, except cut it.

“I want to look like Nadia,” I told my mother. “You want to be a gymnast?” She asked. “No,” I said. “I want her hair.” She consulted with my father first. Of course, he said No—especially not now. But we went anyway. For my mother, granting my wish was a way of protesting. While openly, she supported my father’s plans to leave the island, secretly, she wanted to stay put. To be clear, I wasn’t envisioning a way to spite my father—he was doing what he thought was best. I was only looking for one way of staying in Cuba. Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was also beginning to understand that hair was, among other things, a gender and ethnic marker. Long, flowing, “good” hair upon arriving in California would mean that I had no questionable ancestry—I’d be one of the white Cubans. Long hair went hand in hand with umbrellas on sunny days to avoid tanning the skin; and short clean nails, as proof of proper hygiene and moral rectitude. All visual evidence of our eventual capacity for quick acculturation in the United States. All ways of distinguishing ourselves from the presumed “riffraff” that was also leaving the island.

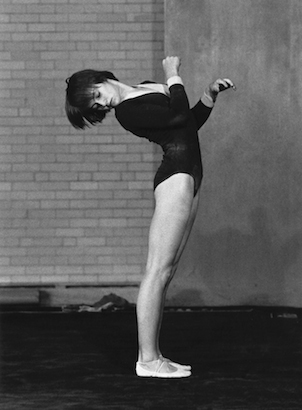

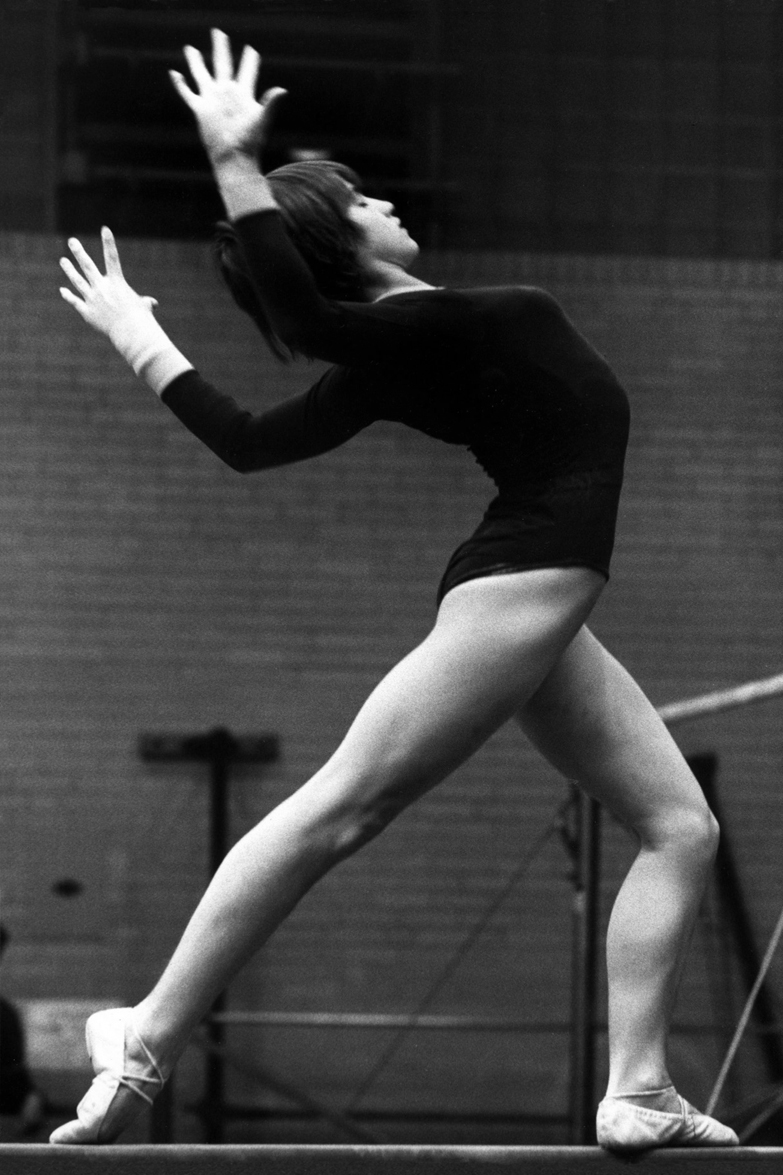

Nadia Comaneci, by Dave Gilbert (1977). https://flic.kr/p/2iTbf

Once at the hairdresser’s home, I sat in a wooden chair in her patio, squinting at the sunlight—anticipating what the new me could accomplish. “Are you sure?” she asked me several times, looking at my mother for confirmation. “Yes,” my mother said. “Go ahead.” “Your dad’s going to kill you,” the woman said. She ran a wet comb through my hair. Tied it into a ponytail at the base of my neck. Made a single braid. She worked the scissors all the way through. About an inch above the rubber band, until she was left holding the braid in one hand. My head threatened to swoon under a newfound lightness. She handed my mother the braid, and let loose what was left of my hair. Gave me thick, heavy bangs and trimmed the rest judiciously to frame my face. At the end, I had a bob right at chin length. My mother didn’t dare cut it any shorter. I flipped my hair this way and that, letting the newly cut edges scrape my cheeks. I reminded my mother that Rafaela Carrá, the Italian vedette so popular on Cuban TV at the time, also had short hair. “Take a look,” the hairdresser said, handing me a round, magnifying mirror—the kind my teenage cousins often used to identify new clogged pores on their nose. It was only wide enough to catch the way the tips of my hair barely grazed the uppermost curve of my shoulder. I couldn’t have been happier.

At home, one look at me, and my father flared his nostrils. Tightened his mouth. “You look like a pumpkin,” he said. It didn’t faze me. Now, I was the proud owner of my own head of hair. During the next few months, my aunt came for us three times, but we didn’t leave. Perhaps my bobbed Nadia hair had nothing to do with it, but I’d like to think that, at the very least, it had managed to postpone the inevitable for at least one more year. A little examination and a little more wistful time spent on what actually took place would reveal, in fact, that there was no magic in Nadia’s hair. But because there was no magic in mobs of angry neighbors, no magic in either staying or leaving, I blamed what little magic there was on something as inconsequential as hair. And yet, the stakes were high: “How should I wear my hair so that we may stay? How long should my hair be, so that my dad will still love me? And the next day, I went right back to combing my hair, strand after strand. I brushed it fifty times, one hundred times, a thousand and one times. I couldn’t pinpoint it then, but something had changed.

Featured Image: Nadia Comaneci, by Dave Gilbert (1977). https://flic.kr/p/2iTe6