Escoria. Flojito. Lumpen. Loca. Gusano. These are just some of the pejorative words that have been used over the past thirty-five years to describe the Marielitos, or the Cubans who entered the United States from the Port of Mariel in 1980. All these words trigger images of an undesirable population, characterized as such by their race, class, sexuality, gender, nationality, ability, and age.

Most people associate the use of these words with Fidel Castro and his regime’s propaganda scheme to stigmatize those who wanted to flee the island’s “glorious Revolution.” While it is true that Castro and the Cuban government crafted much of this language, many people in the United States, including some Cubans who entered the United States in previous waves, came to rely on these words to describe and separate themselves from the Marielitos. Put another way: the construction of an undesirable Marielito came from both sides of the Florida Straits.

Several years ago, I struck a conversation with a group of people I did not know at a party. One of them regaled us with a story about one of his coworkers. I don’t recall the details, but needless to say this man did not think very highly of his colleague. In fact, as he finished his story, he made one last addendum: “You know, he’s a Marielito.”

By no means an isolated occurrence, this reveals a lot about the cultural legacy and memory of the Mariel boatlift. The man at the party believed that by concluding his story with the revelation that his coworker came to the United States during that wave, his audience would surely understand just how bad things must have been at the office. He likely thought his audience would nod knowingly, as if his statement conjured up both an accepted and popular narrative of the undesirability of the Marielitos.

He also, like so many others, distanced himself from the Marielitos by designating them a particular identity group. That is, his coworker was not merely a Cuban who came on the Mariel boatlift. He is a Marielito. No past tense. He had acquired a very particular, albeit undesirable, identity in this circle. Calling someone a Marielito carried a derogatory connotation. It too was a pejorative.

This identity-specific association is not entirely anomalous. In places like Miami, it is not uncommon to hear someone say, “Ella es una de las niñas pedro panes [She is one of the Peter Pan girls]” to refer to the wave of roughly 14,000 young people who entered the United States in the early 1960s as part of the Operation Peter Pan flights.

McDonald, Dale M., 1949-2007. Cuban refugees on board boat during the Mariel Boatlift – Key West, Florida. 1980. Color photoprint, 6 x 5 in. (State Archives of Florida/McDonald)

In many ways, the corresponding wave of Cuban immigration defined an individual’s identity in the city and beyond. Cuban-Americans often ask other members of the community when they left the island. This represents a desire to share common personal experiences and create community. It has also been used to map out an individual’s past. This could include preconceived ideas concerning her or his class, race, and sexuality, for instance.

For these reasons, I have heard Marielitos play all sorts of linguistic Olympics to evade being identified with this particular wave. Vague responses often prevail. This includes responses such as, “Yo vine en los años 80 [I came in the ‘80s]” or, “Tu sabes, cuando cambió todo en Miami [you know, when everything in Miami changed].”

To this day, the immigrants’ association with crime, vagrancy, homosexuality, and disability informs much of the Mariel narrative as “evidence” of their undesirability. It is often cited as an example of U.S. immigration policy run amok. Many nativist groups, including the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), pointed to Mariel as an example of how loose or lax border control ruined the nation. According to this popular perspective, it exposed leaks in a broken welfare system, an overly generous and naïve U.S. entrant policy, and the immigrant takeover of U.S. jobs.

In today’s political climate—with Republican presidential hopefuls in particular, such as Donald Trump, employing an image of an imagined Latina/o migrant menace—the need to set the record straight is of even greater importance. If anything, the Mariel legacy has shown us just how powerful metaphors and stigma can be in shaping policy and reform.

For many, the Mariel boatlift appeared to be another example of Cuban exceptionalism, or the privileged status of the island nation in the U.S. imaginary and its policies. If we dig a little deeper, and historicize current events like the Central American or Syrian refugee crises, we see common threads that make Mariel appear far less exceptional.

Thirty-five years later, we are long overdue for a major reassessment of the affair. In December 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro announced they would restore formal relations between the two nations. What this might mean in terms of conducting new research and augmenting our understanding of post-1959 events like the Mariel boatlift remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, the Mariel boatlift continues to be a cautionary tale in both the United States and Cuba. For the former, it is cited as an example of the so-called dangers of porous borders and weak presidents who let other nations get the best of the United States’ generosity. In Cuba, Mariel represented a nationalist consolidation and aggressive demonstration of what it meant to be a “true” revolutionary in the face of social and political turmoil; which became manifest in the island’s racist, ableist, and homophobic purging.

Both these perspectives often erase how the boatlift either served or failed to serve the needs of a group of people largely reduced to an image of metaphorical garbage neither nation-state really wanted. This dossier, then, contributes to revising and dismantling the many myths of Mariel, and focuses on both personal and collective experiences that were otherwise ignored by popular media. These works–whether an interview, analysis, photograph, or personal essay–add depth to the lives of those who experienced Mariel first-hand. For them, this history and its memory has never ceased–and was always more than myth.

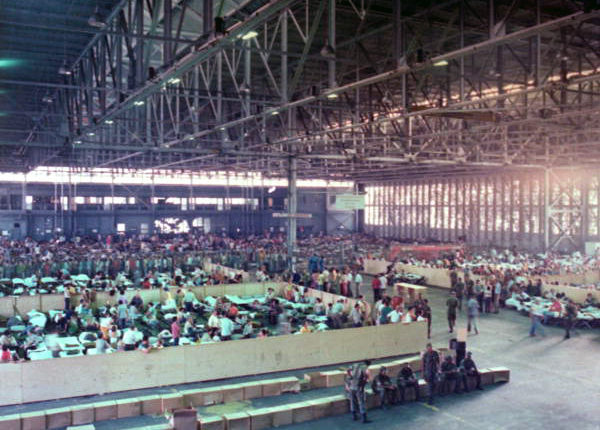

Featured Image: McDonald, Dale M., 1949-2007. Cuban refugees from the Mariel Boatlift being temporarily housed in seaplane hangar at Trumbo Point – Key West, Florida. 1980. Color photoprint, 4 x 5 in. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. , accessed 1 August 2016.