Every presidential election turns South Florida into a battleground. Florida is a swing state, and Greater Miami is its most populous region. Most voters there are Democrat, but about 25% of them are unaffiliated and up for grabs. As Election Day nears, the two major party candidates are neck-and-neck, and they and their surrogates have descended on Miami to fight for the swinging Cuban vote. Among the area’s overwhelming Hispanic majority, Cubans are the most numerous group (a third state-wide, and more in South Florida) and a powerful voting bloc, with great political, financial and media power. Traditionally Republican, they increasingly lean Democrat thanks to a U.S. born generation as well as newer immigrants who favor fluid communications with Cuba. In fact, the Cuban stronghold of Hialeah –home to about 300,000 people, mostly Cuban- went for Obama four years ago, despite the city’ self-proclaimed Republicans leading in City Hall. But will it also go Blue this year?

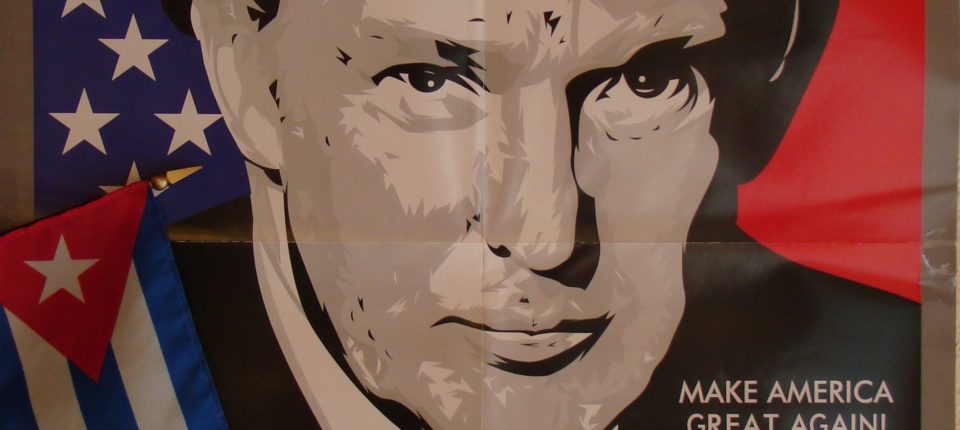

Merely a few days before the count, some polls claim that Donald Trump is up by several points in Florida, while others ascertain that as many as a quarter of Republican early voters are crossing party lines. But who will ultimately win is anyone’s guess and it may come down to the Cuban vote. Whether or not Trump carries Florida, however, his discourse of power and nation has resonated with many immigrants’ yearning for a nation, at ease with a hierarchical model of society led by a strongman. At the same time, Trump’s personal story has validated the myth of the American dream that inspired many immigrants in their journey. In Miami, while Cuban Americans and a middle class might support Trump on the basis of his economic prescriptions, first generation immigrants might also find an appeal in his ideology of national destiny.

The Battle for Miami

It is not just the old anti-Communist guard. In Miami, among the Cuban political elite and in the low- and mid- income Cuban neighborhoods, from the so-called exilio histórico to recent “balseros,” from the well-to-do to the down-and-out, Trump has followers. The community, however, is sorely divided. My Qué Pasa Hialeah group stopped meeting after some in the group (“the Millennials “) disrespected Donald Trump, or so it seemed to several others. We were a group of concerned citizens from all walks of life: gay and straight, young and old, professors and students, artists and entrepreneurs, mostly Cuban, who came together once or twice a month to plot how to make Hialeah a more livable place: how to promote the arts, and how to turn out voters, when in some elections barely a 5% of the electorate participates. At first glance, other than perhaps age, nothing much distinguished the “Right” from the “Left”- not even funkiness. Some of the ones planning to vote for Trump had the most alternative lifestyles, and although in some cases loyal Republicans, they were also social activists and by no means what anyone would think of as “conservative.” But when the Qué Pasa Hialeah group was rumored to be a Democratic Party scheme, things fell apart, at least until after the election, when everyone will go back to caring about the parks, the arts, the homeless, and the shady dealings of City Hall.

The fracture between those who support “Donald Tronco” and “Hillary Clítoris,” as comedian Alexis Valdés calls them, is as deep as it is messy, and it cuts across friends, relatives and colleagues – although Millennials are more likely to view Donald Trump in unflattering terms, including as a flying pig. “Mom, don’t vote for that man,” pleaded a friend to his mother on Facebook, while scores of others have blocked cousins and aunts and uncles. At times, the confrontation has become physical, as at the very Cuban Hialeah-based America TeVe talk show 90 Millas (90 miles). There, a pro-Trump Cuban American panelist had to be restrained from assaulting another guest who played with Trump’s last name and turned it into “trumposo” (which sounds like tramposo, or cheater). Former Punto y Coma comedian Javier Berridy parodied the situation in an online video that quickly garnered over a quarter of a million views. To the popular “La Gozadera” hit song, renamed as “La Votadera” (The Voting Frenzy), Berridy mocks the average voter’s confusion (“one [candidate] is worse than the other,” he sings], emphasizing the animosity the election has generated: “People are crazy out there, fights everywhere, everyone wants to be right…” In the end, he realizes that he is not a citizen, and so he is spared from the unsavory decision.

The media is also divided. The Miami Herald, like all the South Florida mainstream papers, has gone into high gear against Trump, endorsing a Democrat for president, but in the process throwing its darling senator Marco Rubio under the bus (its Spanish-language offspring El Nuevo Herald, however, still endorsed Marco Rubio). “Donald Trump has managed to talk a good game to fire up frustrated and frightened mostly white Americans,” wrote the Miami Herald editors, without elaborating if those included their Cuban readers. The paper’s veteran Cuban columnist Fabiola Santiago, went as far as calling Trump a clown and a “vulgar chusma-in-chief,” and describing his Cuban supporters as suffering from “Cuban supremacy syndrome.” The fact that Cubans have immediate parole into the country and fast track to citizenship would make them feel superior to other immigrants. Indeed, Cuban immigrants in Miami have an uneasy relation to other Latinos and to black Americans in terms of class, race, and ethnicity, that reveals their own uneasy position within American society. A lot of that is manifested in Spanish talk radio, by and large favoring Trump.

I tuned in to the quintessential exilio station Radio Mambí, on 720 AM, the day (October 24th) when its star host, Ninoska Pérez Castellón, was airing her interview with Donald Trump. Trump was in town that day, speaking first to the Bay of Pigs veterans and then meeting with selected Cuban American leaders, including University of Miami’s History Professor Jaime Suchliki, in Doral. Like Trump’s remarks at both meetings, the interview itself felt scripted and trite, catering to the standard exile views by opposing Obama’s rapprochement as a bad deal. A full-hour of call-ins followed, most of them from older Cubans praising the candidate. It was when the show broke to commercials, that the listener was forced to step back into a Miami that was more than Ninoska’s loyal listeners.

Indeed, every time Trump’s words were interrupted to go to a break, a generically-accented, soft spoken woman called, in one recurrent ad, on “mothers, daughters and sisters” to defend “morals, order, and civility in the home” and ensure “the survival of family and decency.” In another, a languid, also non-Cuban feminine voice, spoke of her sons who proudly served in the Armed Forces, only to convey her fear for that which threatened her love for them and the country they were defending. In both cases, Donald Trump’s vulgarity was identified as the menace to these deeply conservative values of family, motherhood and nation. The messages, delivered in a humble, almost mournful manner, were incongruous with the high-energy show. More to the point, they were unlikely to convince an uncompromising audience of Cuban exiles who referred to Clinton as la vieja esa (“that old woman”), and whose foremost concerns were not about private morality but about restoring the might of the American Empire and bringing the Castro government to its knees.

The exilio histórico’ support for Trump was a given. From Spanish talk radio, to public manifestos (like that of the 92-year old soap opera writer Delia Fiallo making the case that Clinton wants to impose a Soviet-type regime, Obamacare being exhibit #1), to demonstrations in front of the iconic Versailles Restaurant in Calle Ocho, the aging Cuban exiles have made the case for Trump on the basis of U.S. Cuba policy and historic resentment against the Democratic Party. The memory of Bill Clinton forcing Eliancito’s return to Cuba is still fresh, and the vote against him, and by extension his wife, is an emotional one. But Trump needs, and has, more votes than they can deliver.

Mainstream Trump

As an anthropologist, I could not help but smile when Maureen Dowd, while recently promoting her latest book, mocked her fellow journalists in their search for the authentic native; now refashioned as a Trump voter. “It’s so funny, because all of my fellow Times columnists have been going on these Margaret Mead road trips,” Dowd said. “‘We’re gonna find this strange, exotic creature called the Trump voter, and try and understand who they are, and reason with them.’” In Miami, however, Trump voters are by no means exotic. What is baffling is, precisely, their ubiquity.

On Sunday, October 30, 2016, I persuaded a friend with a good camera and an even better eye to go to Hialeah’s central library, where there was early voting. There, we found Raquel-Regalado-for-mayor activists, Mario Diaz-Balart flier handlers, and lots of signs on fences and grassy areas surrounding the building, but none for either of the presidential candidates. Then, in between parked cars, behind an older woman sitting at a camping chair and surrounded by signs of local races, we spotted three signs with the Trump/Pence logo on them. One for Hillary appeared at a fence behind another car. It seemed that Hialeahns cared a lot more about local issues than about Washington affairs. Where were the Hialeahns for Trump?

We decided to pay a visit to the local Trump office, two blocks away.

It was a small, nondescript brick building, fronted with flowers. We walked up the three stairs and pulled the door open, only to find an altar with photos of Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, and Barack Obama, and a handmade cardboard sign that read “the real deplorables.” The main office was ample and tidy, with imitation-wood walls and flower bouquets here and there that gave it an old heartland vibe. There, several elderly women were phone banking. Unlike in the Bernie or Hillary campaigns, where volunteers use laptops and a special software program to dial in numbers, they were using landline telephones tied to the wall. In another room, two more women, one clad with an Islamic headscarf, were sitting side by side, also making phone calls.

Back in the main room, one of the women asked for our phone numbers (they did not do email) and offered us yard and knob signs. We declined the latter, and they nodded, as if understanding that we would not want neighbors to know. Having canvassed for Obama in Hialeah four years ago, I knew that people did not want to be outed for the Democrats. Yet Obama carried Hialeah, however narrowly. Now the tables were turned. Many people would vote for Trump. They were just not saying it out loud. And they were not volunteering. Most of the volunteers did not seem to be from around. They spoke little or no Spanish, and when another was dispatched to the library with more Trump signs, she requested directions (200 yards down the sidewalk).

This was definitely not the boisterous Cuban atmosphere we expected. When a middle aged couple walked in for bumper stickers, we took the opportunity to wave goodbye to the affable ladies. We got on the Jeep and set the GPS to our next stop: a “Cubans 4 Trump flash mob” in Miami Lakes, a well-to-do suburb of Hialeah.

By the time we arrived at the corner of Miami Lakes Drive and 77th Ct, the rally was in full swing, with people along the sidewalk and the median euphorically holding up their Trump/Pence signs. The controversial mayor of Miami Lakes –recently acquitted of federal bribery charges– had just paid a visit to show support, and cars blew their horns as they drove by.

This was a cheerful bunch: most of them families with children, bilingual, white, born in the U.S. or here since childhood, and living nearby – in an area with a median income of 62k and a median housing price of 228k (both more than double than Hialeah’s). They were friendly, happily agreeing to pose for photos. Some of them said that they had supported Bush in the primaries, others Rubio, and only one told us that she had been for Trump since the get-go. Yes, they were aware of Trump’s flaws, but “la” Clinton was just not an option.

One generation removed from the exile trauma, their discourse, concerns and views were within the Republican mainstream regarding taxes, business, immigration, etc. The Cuban flag was absent from their sign and from their rally, while the U.S. flag was there but with measure. These “flash mobsters” neither looked to Cuba nor needed to assert an Americanness that they took for granted. In this respect, they differed from more recent Cuban immigrants -like many Guantánamo balseros— whose Facebook pages yield U.S. flag after U.S. flag, and photos of themselves, now middle aged, proudly showing iconic sites of U.S nationalism. Some of them, members of various Cuban immigrant Facebook groups, can be seen in military fatigues and carrying guns – in one case, undergoing militia training in the Everglades- and unequivocally supporting Donald Trump. These images seemed to be worlds away from the Miami Lakes middle class, however. The very fact that their rally was in a distant suburban road is also telling. Unlike old exiles and new immigrants, both of whom typically took their grievances to the downtown Freedom Tower – the iconic building where exiles were processed into the U.S.- the Miami Lakes crowd did not feel they needed to make the additional statement of taking on a symbolic space, beyond their suburb’s most transited corner. That alone indicated their taken-for-granted belonging to the U.S. nation.

As we left the rally, we waved goodbyes to the new friends who invited us to a teaparty gathering the following Sunday as nonchalantly as if it were a family picnic.

What united all these people in Trump?

It was another one of Ninoska’s callers at Radio Mambí who offered a clue. “What we need after this eight years of Obama, is a man who wears the pants,” he said, and not “la vieja esa” (the old hag) who would faint at the sight of the first terrorist that crossed the border. Trump would fight him instead, as if terrorism was to be fought body to body. Clinton, like Obama, was portrayed as weak. “Obama was not even received by Castro at the airport,” Trump complained to Ninoska. Had it been him, he said, he would have gone back into the plane and told the pilot, “come on, we are going home.” Clinton too, had been taken for a ride by Castro back in the 1990s, heard Trump over and over in his community meetings with exiles.

It was Trump’s bravado’s that made him appear as a leader. Many people shared his view of Obama’s weakness before Raúl Castro, and he knew it was safe to praise Raúl Castro as more of a leader than Obama; even in a context in which praising the Castros is a sin. It is no coincidence that a city like Hialeah has a “presidentialist” system with a strong mayor who is also the city manager: its first Cuban mayor held on to his post for a full 24 years (1981-2005). Trump’s white male authority signifies a restoration of order in a fragmented Cuban society still finding its place within the United States. As a businessman whose supporters refuse to see as less than successful, he is the embodiment of the American dream and a living proof that neoliberal tax policies allow just about anyone to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and reach the top. Thus, to new cohorts of Cuban immigrants, Trump represents hope better than Obama, because he promises self-reliance.

Most importantly, Trump has shifted political discourse away from expert knowledge and elevated it back to the superstructure, the realm of ideological rhetoric. In so doing, he allows for many different people to connect to it, regardless of their actual politics. What is at stake is the nation itself: its boundaries and the exclusion of those who have traversed them unceremoniously, without undergoing the proper initiation rites. Trump, like no other candidate before, has tapped into an unfulfilled need for collective nationalist expression in a country that is laissez-faire in that respect. In addition, as a modern ideologue, Trump has also connected the nation to the modernization and industrialization enterprises, weaving a type of narrative that theorist Svetlana Boym called “restorative nostalgia.” That is, he is proposing a continuity with a past vision of the future; the vision that the Founding Fathers and other gentle folk were said to have imagined for the country’s greatness. In this sense, Trump’s view is essentially utopian.

After the election, even if he loses nationally, he will have provided his immigrant constituency with the means of expression for non liberal understandings of the polity, otherwise delegitimized. These understandings, concerning patriotism, hierarchy, authority and order, will remain above ground if only because they are national universals. This is a battle for the nation, for the American nation, and the survival of Cuban exceptionalism within it.

Photo Credits: IVG (Ivana Blanco Gross), AHR (Ariana Hernandez-Reguant), and PP (Petra Pieters). Video by Petra Pieters.