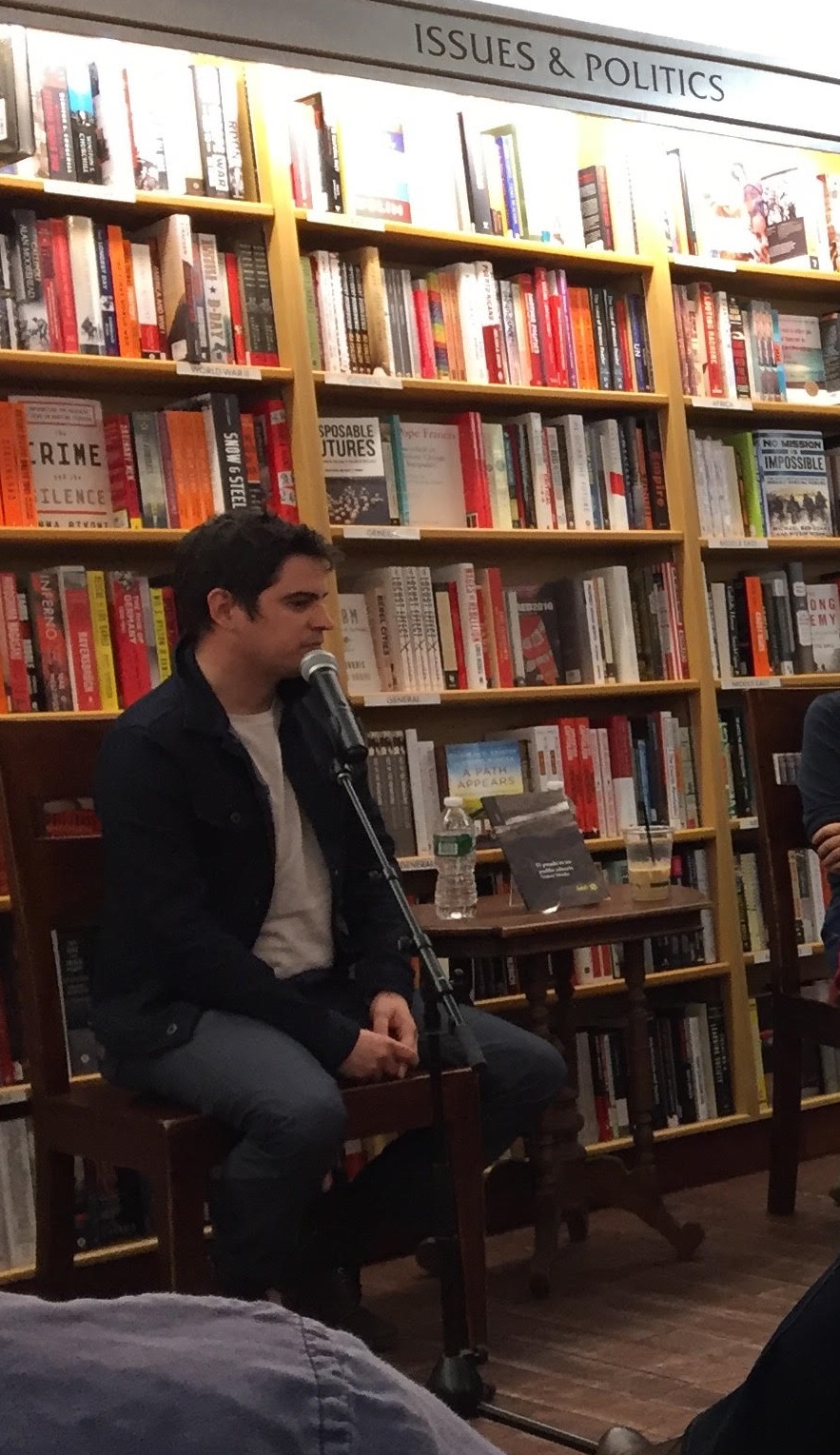

In the book, hot off Bokeh Press, El pasado es un pueblo solitario (The past is a lonely village), Osdany Morales’ poems emerge as if they are the answers to computer-generated questions to help users recall their online passwords. All of these questions are written in English, and the responses -the poems- are in Spanish. Listening to Morales the other night at McNally Jackson Independent Booksellers in NYC, I could not help but think of the implications for translation of his poetic approach.

J.L: Would you call your poems bilingual? Do they require a bilingual reader? What is the result of this juxtaposition between this performance of robot-like English, supposed to be understood by all within the confines of the Internet, and the Spanish of your poetry?

O.M: When I wrote this book my knowledge of English was quite rudimentary. Let’s say that I was all that was the opposite of fluent, that term with which efficiency in language is commonly recognized. Fluency would seem to imply a particular velocity of not only diction but also of comprehension, and ultimately, of capturing, not the speaker toward that language, but rather, the reverse, the language toward the speaker. I believe the reader of my book of poetry belongs to that same moment of resistance to fluency. What is fluent, in this case, what is fluid as a substance with no fixed shape, is memory.

The bilingual reader has the apparent advantage of contemplating with even more clarity the interrogation scene. If the reader is not bilingual, s/he doesn’t lose, because of that, his or her status as reader. Rather s/he may recognize characters, identify the language in which they are written, and in some cases, understand a few words or incomplete questions. The questioning then becomes more demanding. When I decided to give in to the interrogation that structures this book, there were questions that I myself didn’t totally understand.

J.L: I also pondered how to translate such poetry into an English dominated text. Have you any advice? How might the alienation that you execute be reproduced? This book seems quite resistant to translation, in part because of the role of American English within the Internet and the reality of this in the world beyond the Internet. Is there any way for that robot-like, anonymous yet powerful language of benign interrogation to be translated into Spanish? Would it be today’s Spanish? And whose Spanish?

O.M: The paradoxes regarding the translation of this book do accentuate the hierarchical relationships that languages establish. The first thing that occurs to me is the easiest of “solutions”: a bilingual edition (I’m already seeing the difficulty of using this word without stretching out the meaning of “bilingual”) that is accompanied by the original, where my approach toward language can be easily discerned. Another way of translating the book would be to repeat the logic but in the opposite sense articulating the questions in Spanish and the poems in English, but the result might be a bit ironic, considering that the scene of being continuously interrogated by a machine in English today is perceived as natural. Writing on social media, for example, always presents those nebulous questions: Facebook’s “What´s on your mind?” or Twitter’s “What´s happening?” However, my book is not dealing with everyday questions; these are security questions, which imply a journey toward that machinery, beyond the Internet. That artificial security speaks in a particular language, and what it asks for in exchange is personal information.

The most radical solution would be to keep the poems just as they are and to frame the book as already translated. That is to say, not even translated, but original. The Anglophone reader would certainly better understand the questions, but since they are questions that s/he too has had to answer, perhaps they would also trigger some kind of individual memory that could find their way within the words or phrases that s/he may grasp onto in Spanish.

J.L: The book is apparently structured in three parts according to questions geared toward early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, with questions such as “What was your childhood phone number including area code? (e.g., 000-000-0000),” “What was your high school mascot?”, “In what city or town was your first job?” Clearly these formulaic questions suggest a continuity and a normality anchored in the United States, rather than the diasporic existence that you and so many others inhabit. Your answers transport readers to a world where the closest telephone is on the screen, alcohol somehow supplants mascots, and labor is linked to ruins. Could you talk about what is being supplanted in the movement from carefully inscribed words in quantified formulas to poetry?

O.M.: The particular form that each poem inhabits, the very fact that the poem “happens,” is the result of disobedience with regard to the English of the questions and of the difficulty of responding to the model of routines presumed in them: to have a pet, to know in which country one wishes to retire, to remember where s/he was when first finding out about 9/11. That’s why I mentioned before that a displacement occurred toward that ubiquitous place in which questions are formulated from different directions, as you say, but always gesturing toward the same scheme of memory. Not to have a direct response for those questions doesn’t mean that the same question doesn’t activate, by opposition or comparison, a specific moment, a parallel temporality whose contrast only reveals itself in fragments, in tangents, in stories. It’s a book of poetry about stages of my life, but also about a country, Cuba, in a very specific moment, wherein the majority of those questions did not make any sense.

J.L.: With your advice in mind, here’s my attempt at translating one of your poems, which I must add, are always very precisely visual—with the question on the left page and the answer on the right. Most importantly, for our readers, I’d like to say that the concept of “retirement” that we have in the United States does not actually translate to Cuba where, for one, in 2014, pensions averaged around $11/month, and the concept of mobility—at least historically—has been extremely limited by the revolutionary state’s limits on housing, and also by the obvious fact that Cuba is an island nation in the tropics where the “U.S.” notion of retiring to a place with a good climate and fewer taxes simply doesn’t apply.

Translation #1 (The Original):

IN WHAT CITY AND COUNTRY DO YOU WANT TO RETIRE?

en lo ancho de la calle veía ranas

en la explosion de las gotas

de lluvia sobre la acera

ranas efímeras, traslúcidas

en cada gota estrellada

todo un imperio

le pregunté a mi madre

¿VES LAS RANAS?

mi padre traía su técnica y yo la mía

a la ronda nocturna de COHETES DE PAPEL

los suyos parecían aves prehistóricas

los míos insignias del futuro

la traza luminosa del vuelo

de aquellos papeles renacentistas

iba dejando un árbol derribado

que nacía de mi padre y de mí

Translation #2 (The Irony):

EN QUÉ CIUDAD O PAÍS LE GUSTARÍA JUBILARSE?

right there on the street I saw frogs

in the explosion of the drops

of rain on the sidewalk

ephemeral frogs, translucent

in each drop that crashes

a whole empire

I asked my mother

DO YOU SEE THE FROGS?

my father brought his technique and I brought mine

to the nocturnal round of PAPER AIRPLANES

his looked like prehistoric birds

mine insignias of the future

the flight

of those renaissance papers

luminously traced a demolished tree

that was born from my father and me