Visual Artist Nestor Siré has set up an art gallery in today’s most popular Cuban media. El Paquete is a 1 Terabyte size changing database of digital content, mostly pirated, and transferred informally through USB external hard drives. El Paquete is nothing like television, any form of radio, or the Internet. A media phenomenon that is run through hand-to-hand distribution, it is outside of government control. It is there that Siré has managed to insert an art gallery.

WHO IS NESTOR SIRÉ?

Nestor Siré is a 28-year-old artist, based in Havana, who is concerned with technological mediation as a creative process. His grandfather redistributed Corín Tellado’s best-selling romantic novels, pirated films in Betacam videocassettes, and most recently, traded a variety of entertainment media in CD format. Influenced by this family background, Siré’s early artwork gave visibility to the creative transformation of media. For instance, in Signage (2009), he encouraged citizens to creatively engage with space by placing signs in public parks that blurred the distinction between private life and public rhetoric. In Shared Link (2014), he launched an artists’ contest via email. The winners, judged by a jury of renowned art critics, shared Siré’s exhibition spot at the 6th Cuban Contemporary Art Salon (2014). By the time of the opening, an online exhibition was also launched. Shared Link questioned the validation processes of the Cuban institutional art system and highlighted the strength of social networks, both offline and online.

In Combos de Video, the art project that preceded his recent work on El Paquete, Siré produced four CDs by working closely with El Paquete’s creators. Combos de Video documented through video Havana ordinary life and the people’s creativity to overcome scarcity. Siré distributed Combos for free in several CD shops around Havana. Moreover, he inserted the piece within El Paquete. As in most of his pieces, in Combos de Video, Siré does not explicitly state a message. Instead, he seeks to expose the politics of everyday life as a communicative process of mediation.

THE GALLERY

The Art section that Siré established in El Paquete is renewed every month and organized as a gallery, on the one hand, and as a series of informational materials, on the other. This latter includes several subfolders with a calendar of events, news, and other files. At Gallery, where he displays his curatorial philosophy, he launches solo shows by individual artists. For El Paquete’s average consumer, Siré explains, “[these shows] might be difficult to understand because they are deeply involved with inquiries related to contemporary art today [. . .] and also because they greatly push the limits of what classifies -or not- as Art.”

The Art section that Siré established in El Paquete is renewed every month and organized as a gallery, on the one hand, and as a series of informational materials, on the other. This latter includes several subfolders with a calendar of events, news, and other files. At Gallery, where he displays his curatorial philosophy, he launches solo shows by individual artists. For El Paquete’s average consumer, Siré explains, “[these shows] might be difficult to understand because they are deeply involved with inquiries related to contemporary art today [. . .] and also because they greatly push the limits of what classifies -or not- as Art.”

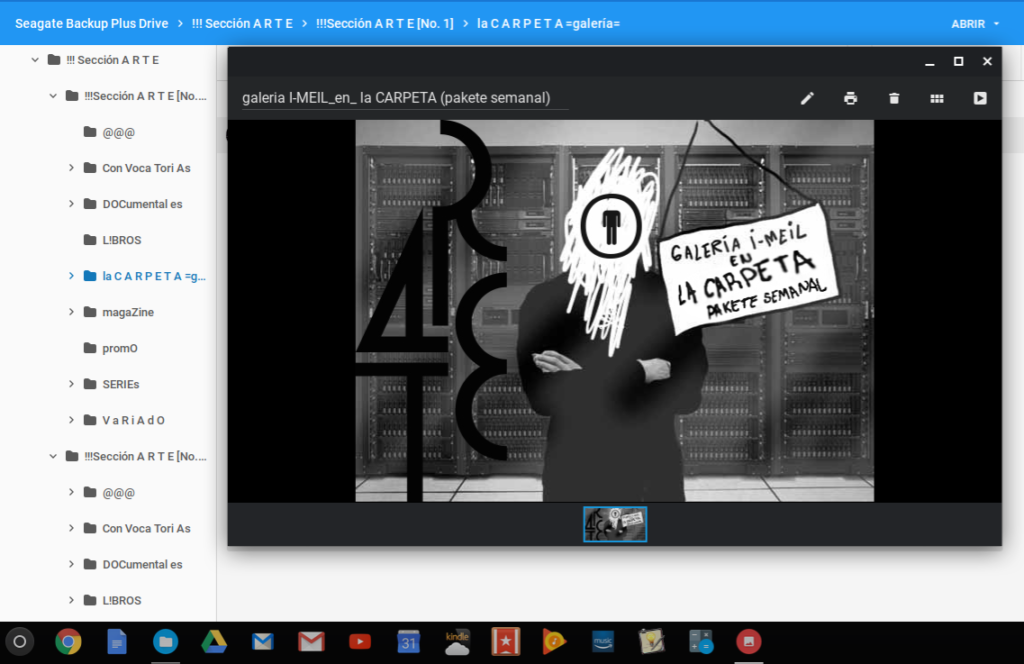

In its first year of 2016, the Gallery section has included works by the award-winning contemporary artist Lázaro Saavedra, as well as younger creators and foreign artists. The series started with Galeria I-Meil, Saavedra’s graphic commentaries on the Cuban political landscape, sent periodically by the artist to a mailing list of Cuban public figures (artists, writers, and politicians). Galeria I-Meil was first launched in 2007, generating the public debate that would be later known as the “Little Email War.” In addition to serving as a clear homage to a tutelary figure in Siré’s career, this opening commented on El Paquete’s Gallery. Galeria I-Meil generated an alternative virtual space to distribute art, but it also triggered an open political discussion that couldn’t take place in an actual gallery. It was a door that opened at the right time, in the right place. What I believe that Siré is telling us is twofold: that El Paquete is, in fact, the Cuban public space today and that a gallery as well as a public sphere should be imagined outside the boundaries of the political and cultural elites.

Screenshot of artist Lázaro Saavedra’s Galeria I-meil.

El Paquete’s Gallery folder also commented upon this grassroots media as a social phenomenon. That is the case of Debugging Nauta and Becoming a Fair Seller. Debugging Nauta, by new media young artist Yonlay Cabrera, was a compilation of errors in the network system Nauta, the one that is used to connect to the Internet on the island. While system errors generally only circulate among the State official network administrators, Debugging Nauta (to debug is to find and remove errors in a computer system) socialized this sensitive information through El Paquete, a media accessed by a large portion of the population. Surely, there is more than one programmer amid the vast audience of El Paquete’s consumers, and likely, a few who originally designed Nauta for the Cuban State. That is to say, the intended socialization goes beyond the unveiling of a commonly hidden transcript; it subtly argues for the collective capacity and responsibility to improve the only way that Cubans have to access the Internet.

Becoming a Fair Seller, by Argentinean video artist Julián D’ Angiolillo, has a different appeal for El Paquete’s viewers. Becoming a Fair Seller consists of the filming, projection, and artistic intervention in an Argentinean market of pirated goods. D’ Angiolillo documented the fair only to project the film for the traders and general participants afterward. The artist also invited them to pirate and commercialize the movie in which they were the featured performers. This piece reflects broadly on piracy as a subversive practice, yet its location in the Gallery folder encourages the Cuban spectator to think about El Paquete’s economic and social dynamics. After all, this Argentinian artwork and El Paquete operate in a similar fashion. Both are the outcome of capitalizing common practices in contexts where the economic fluidity depends more on informal networks than on the official sources of private companies and the State.

CURATING WORDS

Not only does Siré curate visual art, but also creative writing. In his Gallery folder, he has included a journalistic contribution by young writer Yoe Suárez, and a one-time Literary folder by an unidentified group of authors.

Suárez’s Your Name is Not Desert narrates the complicated relationship between the Cuban State and the Protestant Church from 1949 to 1999. Talking to Lord Cuba, the second book by the same author, is a compilation of interviews with Cuban writer Humberto Arenal (1926-2012). In addition to the significance of the topic of the first book, Your Name is Not Desert fills a gap in Cuban journalism since it is based on actual research. The second title is a more modest contribution, despite its testimonial value, as it focuses on Arenal’s personal life and encounters with mid-20th century literary icons, such as Virgilio Piñera and Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

The literary exhibit consisted of a folder entitled “The Literature Folder,” in which there were seven subfolders of compiled digital material: “Theater,” “Magazines,” “Universal Literature,” “Illustrated Children’s Books,” “Comic-Manga,” “Literature and Cinema,” and

“Science Fiction.” “Except Science Fiction,” “Illustrated Children’s Books,” and of course, “Universal Literature,” all the writing is by Cubans. “The Literature Folder,” assembled by a group of anonymous writers, is concerned with the national mechanism for literary production and distribution: “If there are still readers out there, El Paquete is where they are.” More importantly, it is about the disconnection between writers and readers in the current Cuban context.

WHAT NEXT?

As for the future, New York-based artist Julia Weist is preparing a work for The FOLDER =Gallery= in collaboration with Nestor Siré. This upcoming edition will be launched next September, simultaneously with a parallel exhibition at the Queens Museum. Weist’s idea is to produce a series of videos featuring “individuals of high interest to El Paquete audience, famous figures spanning music, film, sports, broadcast and culture” (personal communication with the artist). The celebrities will address the camera, say “hello” to El Paquete viewers in their personal way, and browse the Internet for 10 or 15 minutes to share their online habits. These videos will be valuable in two ways for El Paquete’s audience. First, they will reveal to the fans the celebrities’ Internet consumption habits, and second, provide online information in an offline media that is meant in part to compensate for the island’s lack of Internet access.

THE IMPACT

When I ask Nestor Siré about the social impact of El Paquete’s Art Section, he answers: “El Paquete as a whole, will eat the Art Section for breakfast.” Siré’s forehead wrinkles as he looks at me. “I am sure that we, as artists, are far away from those who will do the decision making about who gets a slice of the cake, I mean, if capitalism in its fullness finally arrives.” His eyes are open wide as he continues. “By then, the strongest part of this society will be the people, people like those who created El Paquete.” I nod my head while closing the computer. We have now finished the interview, and it is close to 6:00 pm. Some neighbors come over to exchange cell phone apps, so we move from the living room to the terrace. “And you know, it is not about one individual or group; it is about social practices,” he adds, sitting in one of my Rebar chairs.