Described by its organizers as “the most comprehensive and significant presentation of modern and contemporary Cuban art shown in the United States since 1944, when the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented Modern Cuban Painters,” Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950 displays over one-hundred works by more than fifty artists whose careers have developed on the Caribbean island after the 1959 revolution. The exhibition is curated by art historian and curator Elsa Vega, independent critic and curator Gerardo Mosquera, and artist and fine arts professor René Francisco Rodríguez. It covers the span of six decades, and includes painting, graphic design, sculpture, photography, installation, video and performance.

Adiós Utopia, on view at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston through May 21, has not borrowed any works from Cuban institutions, and it relies solely on loans from more than two dozen private collections and museums in North America, the Caribbean, and Europe. Advised by Mari Carmen Ramírez, the Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the MFAH, and Olga Viso, Executive Director at the Walker Art Center, where the show will be traveling next fall, the project has been supported since its conception by the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO Miami) and the Cisneros Fontanals Fundación para las Artes (CIFO Europa), both founded by philanthropist, collector, and principle lender to the exhibition Ella Fontanals-Cisneros.

Adiós Utopia is an ambitious venture that will leave a profound imprint on the local and international exhibition history of contemporary Cuban art. The exhaustive appetite of the project is right for the general public, but its shortcomings are more evident for viewers familiar with the field. The exhibition follows a flexible chronological narrative, and surveys Cuban artists’ constantly in-flux relations with the revolutionary project, and their evolving engagement with the notion of utopia. The show examines early celebrations of the guerrilleros’ endeavor, explores the artists’ later critiques of the revolutionary system and of the ruling class (voiced both from “within” and “outside” the revolution), and analyzes the artists’ most recent disenchantments with the post-socialist program on the island.

The construction and deconstruction of utopia is indeed a pervasive motif within contemporary Cuban art, and a subject that probably also satisfies American audiences’ expectations about the arts from the island. Structured around concepts that connect art and the Revolution, such as censorship and exile, some themes are adequately surveyed, while others could be further investigated. For example, the study of quixotic experiments for the merging of art and design, and of craft and industry, includes a flamboyant display of silkscreen posters, but leaves out projects, such as Telarte and Arte en la fábrica, that involved artists and blue-collar workers.

The works in the exhibition are large, brightly colored, and powerful, and they encompass exquisitely restored pieces, such as Juan Francisco Elso’s 1986 For America (José Martí), as well as a number of works that had not been exhibited since they were first shown and immediately banned in Cuba. These include Tomás Esson’s 1987 My Tribute to Che, in which two beasts fornicate before an image of Ernesto Che Guevara, and Eduardo Ponjuán’s and René Francisco Rodríguez’s jointly created depictions of Fidel Castro executed for the controversial El Castillo de la Fuerza exhibition, in 1989.

The varied style of the works in the show, and their formal and conceptual excellence, reflects the high quality of Cuban art, and the strength of arts education on the island. The works’ social and political significance, however, is sometimes overshadowed by the predominance that the exhibition gives to the appeal of the visual. Thus, there are several monumental pieces in the show, such as Wilfredo Prieto’s 2001 Apolitical, an installation of thirty flagpoles in different shades of gray, and Glexis Novoa’s Soviet-inspired gigantic wooden altarpiece from his series Practical Stage (1989). However, less aesthetically alluring and precarious documentation of guerrilla actions by subversive collectives such as Puré, Grupo Provisional, Arte Calle, and Enema, is nowhere to be found.

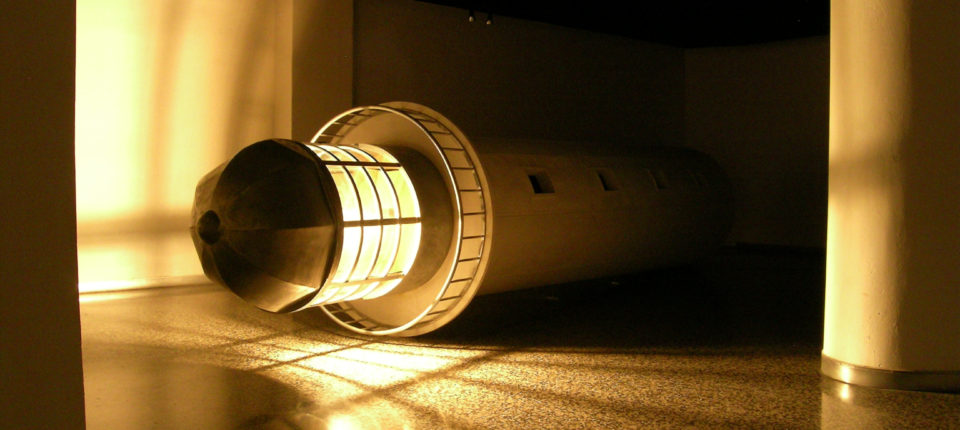

The arrangement of the works in the galleries is sometimes overly unequivocal. The section on discourse, rhetoric, and media is populated with images of mouths, teeth, and tongues. Similarly, one of the two galleries titled “Inverted Utopias” includes numerous literal references to the upside-down: Flavio Garciandía’s horizontal portrait of a young woman lying on the grass (She Is in Another Day, 1975), Tania Bruguera’s 1996 performance video Head Down, and Los Carpinteros’ almost life-size sculpture Fallen Lighthouse (2006).

However, the second gallery within the “Inverted Utopias” section, a title that inevitably brings to mind Mari Carmen Ramírez’s 2004 homonymous exhibition, is one of the most elaborate in the show. Probably departing from the idea articulated by Eugenio Valdés Figueroa, director and chief curator of CIFO, of frustration as a productive premise in many contemporary Cuban artworks, this room points to the impossibility of language as a form of communication. Dwelling on distrust, fear, shame, and hopelessness, these works focus on that which is perceived as unmentionable, and even unthinkable. Lázaro Saavedra’s 2004 The Syndrome of Suspicion is a silent film self-portrait of his own restless eyes, Carlos Garaicoa’s 1997 video Four Cubans shows four Angola War veterans unable, or unwilling, to speak about their experience within the military, and in Iván Capote’s 2003 electric engine installation, Dyslexia, the sentence “life is a text which we learn to read too late” can barely be glimpsed before the machinery repeatedly covers the words with industrial oil.

The extensive bilingual publication that accompanies the exhibition goes far beyond the scope of the show, and includes insightful essays by the curators, as well as by scholar Rachel Weiss, artist Antonio Eligio Fernández (Tonel), and writer Iván de la Nuez, as well as a comprehensive chronology by Beatriz Gago Rodríguez. In spite of the exhibition catalogue, however, the different economic and political periods within the history of the Revolution and their effect on art making remain generally overlooked in the galleries. Thus, for an exhibition that focuses on Cuban artists’ myriad interpretations of the revolutionary project throughout the decades, the conundrums of the Cuban context are generally missing from the picture.

Moreover, significant events and phenomena within the development of “el nuevo arte cubano” are frequently downplayed, such as the role of independent art galleries like Espacio Aglutinador, the impact of the Havana Biennial, and the international experience of many Cuban artists since the first massive migration waves. Furthermore, while some artists have three or more works in the show, several important figures are not represented at all, such as printmakers Belkis Ayón and Abel Barroso, photographers René Peña and Marta María Pérez Bravo, and members of the youngest generation of artists (e.g.: Grethell Rasúa and Adrián Melis).

The last two works in the exhibition, two videos from 2012, present the revolution as a failed project: Los Carpinteros’ Irreversible Conga is a backwards conga in which the dancers are attired with funerary black costumes, and Javier Castro’s Golden Age, in which Cuban children count dictator, tourist, and prostitute among their dream jobs. Indeed, the exhibition title, Adiós Utopia, points to the socialist project on the island as being over. However, bearing in mind that the Castro family remains in power, and considering how often Cuba is regarded as undergoing transition, to what utopia exactly are Cuba and Cuban art currently saying “adiós” to remains opaque. In fact, it could be argued that, today, the island and its artists are actually saying hello to utopia, but to a different kind of utopia: that of capitalism, globalization, and the art market.

Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950 is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston through May 21, 2017. The exhibition will travel to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis from November 11, 2017, to March 18, 2018. Future venues are expected but have yet to be announced.

Cover Image: Faro Tumbado, by Los Carpinteros (courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Houston)

Parallax Image: Ernesto Oroza. From Aachen to Zürich. Video screenshot.